Add Your Heading Text Here

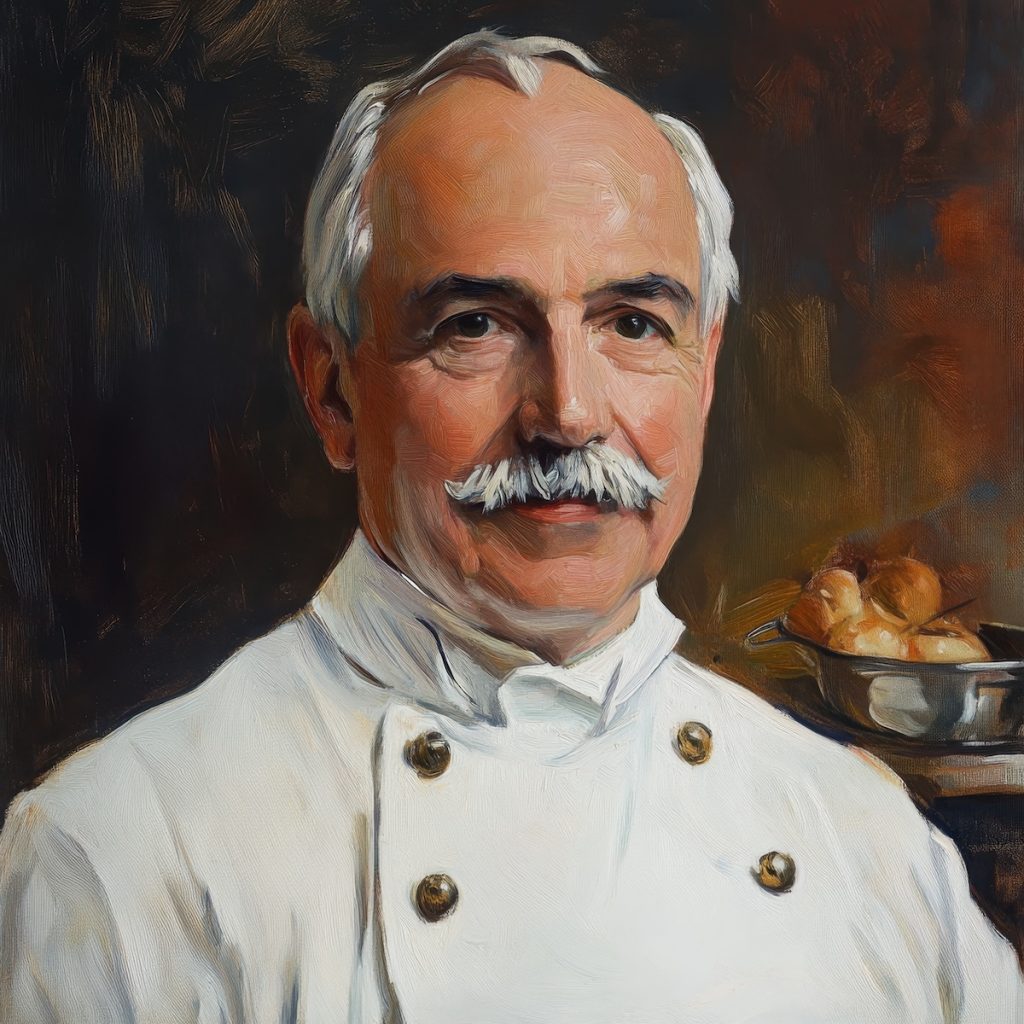

Auguste Escoffier (1846–1935) revolutionized the world of cooking and shaped modern cuisine as we know it. Escoffier brought order, refinement, and professionalism to French kitchens.

He didn’t just cook—he transformed the way chefs worked, creating the brigade system still used in restaurants today. Through his legendary work at the Ritz and the Savoy, he elevated cooking into an art form, striking a balance between elegance and efficiency.

Escoffier took inspiration from the past, especially the towering legacy of Marie-Antoine Carême, but stripped away excess and embraced simplicity. He codified recipes, standardized techniques, and wrote Le Guide Culinaire, the definitive culinary manual that continues to guide chefs more than a century later.

Among his most enduring contributions is the modern classification of the five “mother sauces,” developed by Marie-Antoine Carême—a foundational system that every professional and serious home cook now learns.

In this post, I’ll explore the life, influence, and culinary genius of Auguste Escoffier. From his early days in the kitchens of Provence to his world-renowned legacy, you’ll discover why Escoffier isn’t just a historical figure—he’s a living presence in every well-executed plate of food.

Let’s step into his kitchen and see how one man changed food forever.

Early Life

Auguste Escoffier’s early life in Provence was humble but formative. Born in 1846 in Villeneuve-Loubet, a small village near Nice, he grew up surrounded by the sun-drenched flavors and seasonal ingredients of southern France—tomatoes, garlic, olives, herbs, and seafood.

This regional influence would stay with him for life, even as he moved into the refined world of haute cuisine.

Escoffier’s family was working class, and he didn’t grow up in wealth or prestige. His father was a blacksmith, and young Auguste was expected to help support the family.

At just 13 years old, he began his culinary journey as an apprentice at his uncle’s restaurant, Le Restaurant Français, in Nice. It was there, in the heat and pressure of a small kitchen, that he learned the fundamentals of French cookery: discipline, technique, and a deep respect for ingredients.

The Provence of his youth was rural and seasonal. The markets overflowed with fresh produce, and the cooking was honest and flavorful. Though he would later become a symbol of elite gastronomy, Escoffier’s roots were grounded in rustic, regional food. His genius lay in combining that simplicity with elegance—something he learned first in Provence, not Paris.

Late Teens and Twenties

Auguste Escoffier rose from apprentice to head cook through relentless discipline, talent, and a drive to master every aspect of the kitchen. By the age of 19, Escoffier moved to Paris to expand his skills.

He took a job at the prestigious Le Petit Moulin Rouge, one of the city’s finest restaurants. There, he absorbed the complexity of haute cuisine and refined his sense of timing, presentation, and leadership.

When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, Escoffier served as a chef in the army. The experience taught him how to work with limited ingredients, simplify dishes, and organize under pressure—skills that would shape his career.

After the war, he returned to civilian kitchens with new confidence. Escoffier continued to climb the ranks through skill and professionalism.

By his late twenties, he had earned the title of chef de cuisine. His reputation grew rapidly as he brought order, creativity, and calm authority to every kitchen he led. Escoffier didn’t wait for opportunity—he created it through excellence.

Most Productive Years

After rising to chef de cuisine in his late twenties, Auguste Escoffier’s career accelerated into legend. He brought not only culinary talent to the table but also leadership, innovation, and a deep sense of professionalism that reshaped the entire restaurant world.

Partnership with César Ritz

In the 1880s, Escoffier formed a pivotal partnership with hotelier César Ritz, a visionary in luxury hospitality. Together, they worked at the Grand Hotel in Monte Carlo and later at the Savoy Hotel in London, where Escoffier dazzled British high society with refined, elegant French cuisine.

At the Savoy, Escoffier introduced now-famous dishes like:

- Peach Melba (created for opera singer Nellie Melba)

- Tournedos Rossini

- Melba Toast

His cooking was sophisticated yet restrained—a departure from the overly elaborate fare of the past.

The Ritz Era

After leaving the Savoy (under controversial circumstances involving financial mismanagement), Escoffier and Ritz opened The Ritz Hotel in Paris in 1898 and The Carlton in London in 1899. These hotels became icons of luxury, and Escoffier’s kitchens set the gold standard for service, technique, and organization.

Retirement

Auguste Escoffier officially retired in 1920, the same year he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur by the French government—an honor that recognized his enormous contributions to French culture and cuisine.

After retirement, he settled in Monte Carlo, Monaco, where he lived out his final years. Monte Carlo was a fitting place for Escoffier: refined, elegant, and close to his Provençal roots.

He had spent earlier parts of his career there, including at the Grand Hotel, and found it a peaceful place to step away from the demands of the professional kitchen.

Even in retirement, Escoffier remained intellectually active. He continued to write, refine his recipes, and correspond with chefs and culinary institutions.

He died in Monte Carlo in 1935 at the age of 88, leaving behind a global legacy that shaped fine dining, restaurant structure, and culinary education for generations to come.

Auguste Escoffier FAQ

What is Escoffier best known for?

Codifying the five mother sauces

Creating the kitchen brigade system

Writing the foundational culinary text Le Guide Culinaire

Elevating cooking from craft to profession

Partnering with César Ritz to create world-famous luxury hotels

What were the five mother sauces Escoffier defined?

Béchamel

Velouté

Espagnole

Hollandaise

Sauce Tomat (Tomato Sauce)

What is the brigade system, and why is it important?

Escoffier created a brigade de cuisine, a hierarchy of roles in the kitchen (e.g., sous chef, saucier, pâtissier), which brought order and efficiency. It’s still used in professional kitchens today.

Did Escoffier invent any famous dishes?

Peach Melba (for opera singer Nellie Melba)

Melba Toast

Tournedos Rossini

Chaud-Froid dishes (gelatin-glazed meats and poultry)

Where did Escoffier work?

He worked in prestigious hotels like:

The Grand Hotel in Monte Carlo

Savoy Hotel in London

The Ritz in Paris and Carlton Hotel in London

Where did he retire?

Escoffier retired in Monte Carlo, Monaco in 1920 and remained active in culinary writing and advocacy until his death in 1935.

Did Escoffier receive any awards?

Yes, he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur in 1920—France’s highest civilian award.

What made Escoffier different from other chefs of his time?

He simplified the overly elaborate style of his predecessor, Carême

He emphasized cleanliness, order, and professionalism

He championed better treatment of kitchen staff

He made cuisine more accessible and standardized for training

Did he have any influence outside France?

Absolutely. Escoffier’s influence extended globally through his hotel work in London and Paris. His recipes, systems, and philosophy still guide chefs in top kitchens worldwide.

How much did he make at the height of his career?

While exact salary figures for Auguste Escoffier at the height of his career aren’t well-documented, he was exceptionally well-compensated for a chef of his time, especially given his partnership with César Ritz and his central role at elite hotels like the Savoy, Ritz Paris, and Carlton London.

Did he have children and did they become chefs?

Escoffier married Delphine Daffis in 1878. She was the daughter of a publisher and had a literary background, which complemented Escoffier’s later writing career. Together, they had three children: Paul Escoffier, Daniel Escoffier, Germaine Escoffier.

Escoffier’s children did not enter the culinary profession. They pursued different paths, and while they undoubtedly respected their father’s legacy, they did not become prominent figures in the field of gastronomy.